Concerning Modern Saints

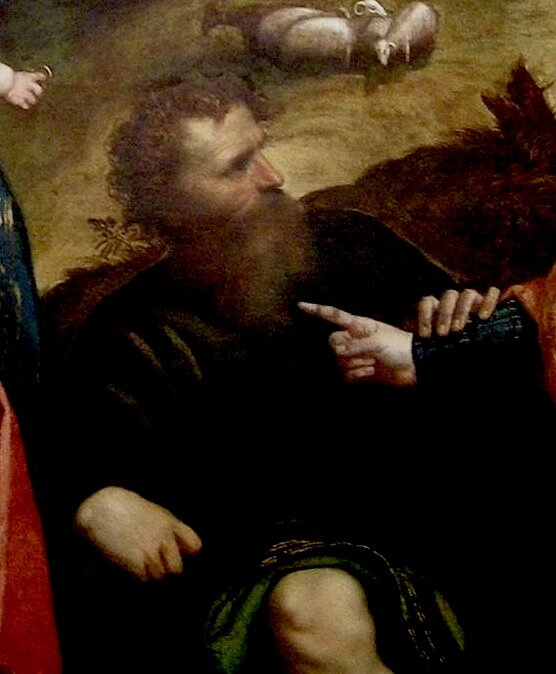

Fra Angelico, Sts. Catherine of Siena and Cecilia, San Pietro Martire Altarpiece, predella

The Church has, from its inception, honored and sought the intercession of the saints. They are venerated properly by dulia, a manner distinct from the worship fitting to God alone, latria. Creation of sacred art to commemorate them and provide a means of communion with them has been approved as far back as 787 by the Second Council of Nicea.

As the corporate action of a social body, i.e. the Church, ought to be regulated by the head(s) of that society, the recognition of the faithful dead as saints was originally made by the local bishop and after 1159 (Alexander III) potentially or certainly after 1634 (Urban VIII), by the Roman See alone. Thus after due examination of a person’s life for heroic virtue, testimony of sanctity and a life worthy of imitation, the Pope will declare such a person certainly a friend of God, worthy of veneration and currently possessing the beatific vision, i.e. is in heaven.* This decision is held by most theologians to be infallible, as a secondary object of infallibility.**

The Catholic Church canonizes or beatifies only those whose lives have been marked by the exercise of heroic virtue, and only after this has been proved by common repute for sanctity and by conclusive arguments. …

It must be obvious, however, that while private moral certainty of their sanctity and possession of heavenly glory may suffice for private veneration of the saints, it cannot suffice for public and common acts of that kind. No member of a social body may, independently of its authority, perform an act proper to that body. It follows naturally that for the public veneration of the saints the ecclesiastical authority of the pastors and rulers of the Church was constantly required.

~The Catholic Encyclopedia (1917), Beatification and Canonization

However the current and preceding claimant to the papal office, and likely back to John XXIII, have introduced and promoted a new religion within the structure of Church. Through a wholesale introduction of new doctrines, disciplines and worship following the Second Vatican Council, they have ceased to be members of the Church or be her terrestrial head. So the judgements and directives of such presumptive popes, e.g. canonizations, are not made by a proper authority and are utterly void.

This is not to say that individuals canonized or beatified by post-Vatican II ‘popes’ are not just and holy and in heaven interceding for us. Only that the faithful cannot know with certainty. Private veneration of undeclared ‘saints’ has always been permitted. Indeed an established cultus has long been an element in the process of discovery for canonization. Thus we find Fra Angelico painting St. Catherine of Sienna, several times, amongst the saints, years before she was officially raised to the altars.

So while the studio’s practice and commitments have developed over time, images of post-Vatican II ‘saints’ remain possible subjects for private veneration and Lord willing, a future, more certain reevaluation of their sanctity. ***

pax

* This does not exclude the very real possibility and even hope that many others, known and unknown, are likewise currently in Paradise. The certainty of their status though is, quoad nos viatores (relative to us wayfarers on Earth), unestablished. See the above regarding private veneration.

**cf S.D. Wright, Dogmatic Suicide – Canonizations, Infallibity and the Consequences

***Some discretion and personal judgement is still reserved by the studio though as not all ‘saints’ enjoy the same purity of reputation and non-infallible ecclesial judgements.